Why Bird Rescue Matters

Every spring and summer, countless animal lovers stumble upon baby or injured birds in their yards, on sidewalks, or near roads. The instinct to help is natural—but knowing what to do (and what not to do) can mean the difference between life and death for the bird.

In the United States, almost all native wild birds are protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA), making it illegal to keep, possess, or treat them without proper permits. That’s why contacting the right professionals is vital.

This guide will teach you how to identify whether a bird needs rescuing, what safe steps you can take, who to call, and how to provide temporary care if absolutely necessary.

1. Baby Birds: Nestling or Fledgling?

Many well‑meaning people accidentally kidnap perfectly healthy young birds. To know if a baby bird needs help, first identify its stage:

Nestlings (Need Help if Out of Nest)

- Few or no feathers, skin visible.

- Pink, vulnerable, unable to walk or hop.

- Should always be in a nest—if outside, they’ve fallen.

What to do:

- Look for the nest nearby and gently place them back.

- If the nest is destroyed, create a substitute small container with soft paper towel and secure it in the same tree.

- Parents will continue feeding them.

Fledglings (Likely Don’t Need Help)

- Fully feathered, short tail, wings slightly stubby.

- Able to hop and flutter, but can’t fly well yet.

- Often seen on the ground being fed by parents.

What to do:

- Leave them unless in immediate danger (cats, cars).

- Keep pets indoors until fledglings learn to fly.

- If unsafe, move them a few feet to a shrub/tree.

2. Injured Birds: Signs They Need Rescue

Call a wildlife rehabilitator immediately if you see:

- Visible wounds or bleeding.

- Unable to fly, dragging wings, unable to perch.

- Tilted head, circling (possible head trauma).

- Obvious fractures or paralysis.

- Covered in oil, glue, or other substances.

- Cat or dog attack (even if no wounds visible, bacteria usually kill within 24 hrs without care).

3. What You Should Do (Step‑by‑Step Guide)

Step 1: Observe First

- Watch from a distance for at least 30–60 minutes.

- Parents might be nearby, returning periodically with food.

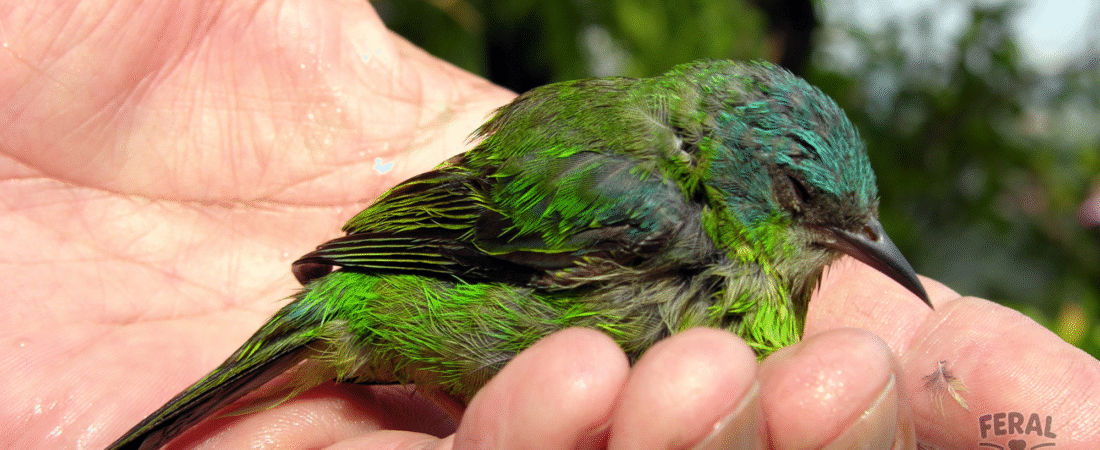

Step 2: Handle with Care (Only if Necessary)

- Use gloves to gently pick up the bird.

- Place in a small ventilated box lined with paper towels.

- Keep it warm (but not overheated) and in a quiet, dark place.

Step 3: Minimize Stress

- No loud sounds, pets, or children near the bird.

- Don’t try to cuddle, handle excessively, or feed “just in case.”

Step 4: Contact Professionals

- Locate a licensed wildlife rehabilitator as soon as possible.

- Never attempt to keep a native wild bird—it’s illegal without permits.

4. What You Should NOT Do

✘ Don’t give food or water (feeding incorrect food is deadly).

✘ Don’t try to raise a wild bird yourself.

✘ Don’t force feed or open the beak—you might cause choking.

✘ Don’t keep it as a pet (illegal & harmful to normal development).

✘ Don’t release injured birds without rehabilitation—they won’t survive.

5. Temporary Emergency Care (Only Until Professionals Take Over)

If you are instructed by a rehabilitator and only as a short‑term measure:

- Warmth: Place a heating pad on LOW under half of the box or add a warm (not hot) water bottle wrapped in cloth.

- Housing: Quiet, dark box with small ventilation holes. No cages (bars risk wing/feather damage).

- No Food/Water Unless Directed: Baby birds usually require species‑specific high‑protein diets every few minutes—impossible to safely provide without expertise.

6. Who to Call

- Licensed Wildlife Rehabilitators: Search via Animal Help Now, or Google “wildlife rehabilitator near me.”

- State Fish and Wildlife Agency: Check state websites for wildlife offices.

- Local Animal Control: They may transport birds to a facility.

- Audubon Society Chapters: Many have hotline numbers for bird rescue advice.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: For federal wildlife concerns.

7. Legal Considerations

- Migratory Bird Treaty Act (1918): Protects over 1,000 bird species in North America. Keeping, owning, or treating birds without permits is illegal.

- EXCEPTIONS: Invasive species like European Starlings, House Sparrows, and Rock Pigeons are not protected, but many states still regulate them.

- Always contact authorities before attempting care.

8. Fun Facts About Backyard Birds

- Baby birds often look “abandoned” when they’re fledglings, but parents remain nearby feeding them.

- Songbirds imprint quickly; human handling can make it harder for them to survive in the wild.

- Birds’ bones heal faster than mammals’, which is why quick rehabilitation is critical.

- Some bird species, like robins, can raise multiple broods in a single summer.

9. Common FAQs

Q1: Can I feed a baby bird bread or milk?

A: Absolutely not. Bread has zero nutrition for birds, and milk can kill them.

Q2: My cat brought me a bird but it looks fine. Should I let it go?

A: No. Even tiny punctures from cat bites almost always cause deadly infection. Call a rehabilitator ASAP.

Q3: If I put the bird back in the nest, will the parents reject it because of human scent?

A: No. This is a myth. Birds generally don’t abandon chicks due to human scent.

Q4: What if I can’t find a wildlife rehabilitator?

A: Call your local vet, humane society, or animal control. They may have emergency contacts.

Q5: Can I keep a rescued bird as a pet if it survives?

A: No, not if it’s a native wild bird. It must go through rehab and proper release. Native birds are wild and deserve freedom.

Final Takeaway

Rescuing a bird is an act of compassion, but handling it correctly is essential.

- Nestlings: Return to nest.

- Fledglings: Usually fine—observe before intervening.

- Injured birds: Contain safely and call a rehabilitator.

Above all, remember: the law protects wild birds for a reason, and professionals have the resources to give them the best chance at survival.

By acting responsibly and quickly, animal lovers can make a real difference for these delicate creatures—often helping them return to the wild where they belong.